By Batsugar Tsedendamba

In 2024, nearly half the world’s population will cast their ballots in various national elections. Healthy information environments are vitally important in ensuring free and fair elections. In vulnerable democratic societies like Mongolia, where parliamentary elections will be held June 28, Russia and China have exploited their significant political and economic influence more broadly to undermine social movements and religious communities that publicly criticize authoritarian modes of governance. They also have weaponized the country’s economic dependence on these two powers that geographically surround Mongolia in an effort to keep Ulaanbaatar in their authoritarian orbit.

In recent years, Beijing and Moscow have forged new (and growing) partnerships in Mongolia’s media sector to launch aggressive propaganda campaigns, depressing open public discourse about these powers’ activities and ultimately undermining free speech. Democratic stakeholders, journalists, civil society activists, and academics must act in concert to safeguard Mongolia’s media and counteract this emerging threat to the information space—both during this election season and beyond.

PRC and Kremlin Influence in Mongolia’s Media Sector

Mongolia’s score on the World Press Freedom index is 59.33—a sizeable drop from its peak score of 74.75 in 2015. While not the only factor, foreign authoritarian influence has had a chilling effect over the country’s media coverage of international affairs. The lack of critical coverage of the activities of China and Russia in Mongolia is likely due to both a lack of space for most newsrooms and agencies to produce journalistic content without external harassment and increased self-censorship by editorial and reporting teams. More broadly, it impacts civil society’s efforts at awareness-raising in the country.

Such self-censorship also extends to the lack of reporting on Chinese and Russian influence operations in Mongolia. In addition to suppressing critical coverage of these powers that impact Mongolia in such significant ways, this dynamic presents challenges for researchers (including this author) to find published data or comprehensive analyses of China and Russia’s role in Mongolia. CCP- and Kremlin-backed influence efforts in Mongolia’s media sector ultimately undermine the integrity of the country’s information spaces when little is published about these regimes other than narratives they proffer from their own propaganda machinery.

China’s Approach to Influencing Mongolia’s Media Space

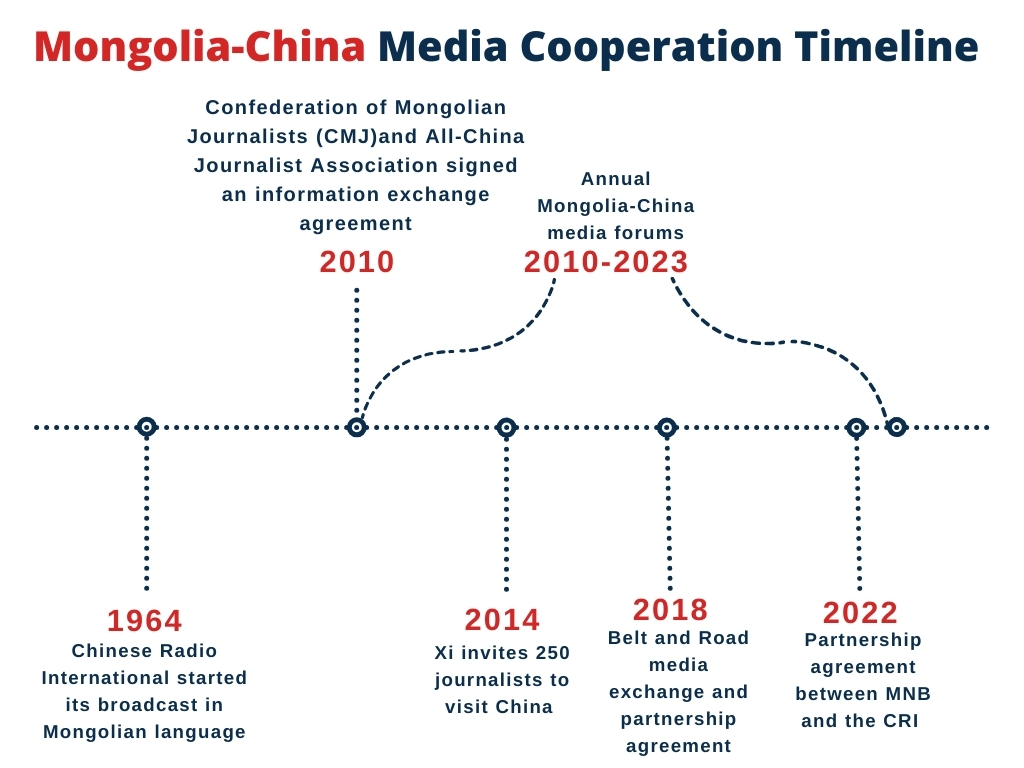

China’s efforts to shape and disseminate preferable narratives date back to 1964, but have intensified over the last decade. For instance, the PRC held the annual Mongolia-China Media Forum for the fourteenth consecutive year, and over one thousand journalists have participated and visited China throughout this period. This figure represents a huge number of journalists for a small country of three million inhabitants. Organized events as part of the Mongolia-China Media Forum include panels that celebrate Beijing’s successful anti-corruption initiatives and efforts that promote technological and economic development.

Joint programs are not the only conduit through which the PRC has influenced Mongolia’s media environment. Numerous Chinese-produced news programs, TV shows, and movies are broadcast on at least six Mongolian TV channels. These broadcasts have been deemed to be part of “Chinese-Mongolian cultural exchange,” yet have had a significant impact over Mongolia’s media sector. Recently, social media content produced by CCP affiliates about economic and social development in China have circulated widely in Mongolian language and social media circles. Beijing-affiliated content is mostly apolitical, apart from advocacy supporting China’s economic development model. Still, its effect in influencing media coverage and popular opinion could be significant as more research uncovers the scale and scope of such content.

Russian Propaganda in Mongolia’s Media Space

Unlike China’s media influence operations, Kremlin-backed efforts focus on more overt political narratives against the United States and the democratic West—and this content has proliferated widely since Russian forces invaded Ukraine. For instance, Russian propaganda has targeted Mongolian partnerships or initiatives with Western democracies. Often, these propaganda materials are translated into Mongolian and disseminated across Mongolia’s media sector.

Unlike China, Moscow generally does not engage in active partnerships or activities with Mongolian media; however, the Confederation of Mongolian Journalists (CMJ) signed a partnership agreement with the Russian Union of Journalists in 2018 to organize information and journalist exchanges, training programs, and collaborative projects, among other initiatives.

Authoritarian Propaganda’s Effect on Public Opinion

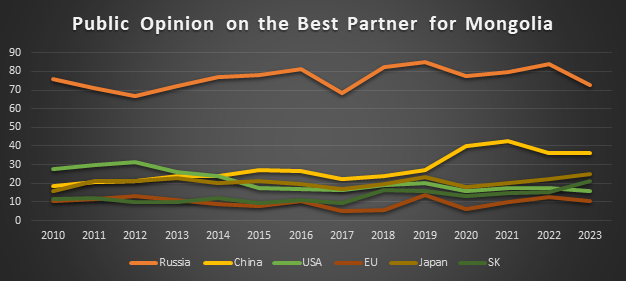

While growing authoritarian influence in Mongolia’s media sector is acknowledged in broad terms, its precise impact is unknown. We can assume that Beijing and Moscow’s actions intend to burnish their image while diminishing the reputation of Mongolia’s democratic partners. Publicly available data supports this assumption and highlights the modest success that Beijing and Moscow have enjoyed in conducting these influence campaigns. According to polling data, public perception of China and Russia has improved among Mongolian citizens. Furthermore, public opinion about the United States as a vital, democratic partner for Mongolia has declined since 2012, as shown in the Political Barometer survey below (2010-2023). Meanwhile, Russia continues to garner strong public support as the country’s ideal geopolitical “partner” despite its ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

Political Barometer Survey 2010-2023, Sant Maral Foundation

What remains unclear, however, is how increased authoritarian influence in the media sector will impact social cohesion, trust in democracy, or support for democratic institutions, processes, and values. Antidemocratic narratives from authoritarian influencers attack a specific (often democratic) country’s image and undermine liberal democratic values and principles. Beijing and Moscow have launched these malign influence operations in democratic societies around the world to great effect. Can Mongolia withstand these authoritarian influence operations or, considering the Mongolian public’s lingering frustration with its government, will the corrosive effects of authoritarian narratives further destabilize the country’s fragile democratic institutions?

How Democratic Actors Can Address Authoritarian Influence and Propaganda

Though Mongolia’s democratic stakeholders, such as those in government and media, have been slow in responding to these threats, it is not too late to act. Democratic actors must come together to safeguard Mongolia’s media and information spaces.

First, the security and free practice of Mongolia’s media sector must be reinforced to repel foreign authoritarian influence and propaganda. Political pressure and censorship, increased criminalization of speech, market and economic factors, and threats to the safety of journalists have limited the ability of the country’s media sector to conduct their work freely. Their difficulty holding state and external authorities to account undermines their ability to safeguard human rights, democratic values, and free speech. Policymakers in Mongolia should initiate reforms to promote the integrity of the media sector and protect it from harassment.

The limited capacity and lack of resources from which media outlets and journalists suffer is another challenge. Political influence of authoritarian-affiliated media and pressure on independent media, as well as economic constraints on the sector more broadly, leave Mongolian independent media outlets vulnerable to malign foreign influence. These constraints challenge the media’s ability to produce quality, impartial journalism. Thus, strengthening editorial standards and policies, increasing fact-checking capacities, and developing new investigative and data-based journalism techniques are vital to enhance the media sector’s resistance to malign influence and propaganda. The leadership of democratic partners and international organizations can make a meaningful and positive impact in this regard.

Authoritarian actors’ increased use of informal, unregulated channels on social media platforms is another emerging issue. Governmental authorities and civil society organizations should enhance their efforts to track, monitor, and potentially regulate such channels. Increased cooperation between Mongolian democracy advocates and global social media companies with support from specialized global NGOs and networks is essential to implement such efforts successfully.

Finally, democratic advocacy can repair the damage authoritarian propaganda and foreign malign influence operations cause. Democratic reformers in Mongolia should make a concerted effort to increase civic education and foster democratic support for the public, youth, and rural communities to rectify authoritarian propaganda’s long-term, corrosive effects on targeted populations. Also, international democratic partners must challenge authoritarian narratives and propaganda while supporting domestic actors in promoting democratic values. Most important, fostering public trust in democratic partnership and solidarity with democratic nations, including Mongolia’s “third neighbors” such as the U.S., France, Germany, South Korea, and Japan, is crucial for isolated democracies, like Mongolia, surrounded by autocratic neighbors to survive and help establish key bulwarks against authoritarian influence.

In a country and society with two authoritarian “giants” as neighbors, only a whole-of-society approach will help address these challenges to Mongolia’s democracy.

Batsugar Tsedendamba is a researcher and civic activist from Mongolia. He is also a former Reagan-Fascell Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. Image credit: hyotographics/Shutterstock.