By Ko Shu-ling

I have been an English language reporter in Taiwan for over 20 years. Many changes have occurred during that time. One thing that has remained the same is the growing influence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Taiwan’s political discourse. Today, this influence is most apparent in the expansion of pro-PRC media outlets in Taiwan. These PRC-backed outlets parrot Beijing’s preferred narratives and promote unification with the island, which China claims as its sovereign territory. Short of war, tools the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has used to advance this goal include military intimidation, diplomatic isolation, and economic coercion. In recent decades, the CCP has also invested heavily in information warfare.

What is the scale of the PRC’s Information Operations in Taiwan?

Eight years ago, Anne-Marie Brady estimated that China spent $10 billion annually on foreign propaganda. These figures are undoubtedly higher today, given the country’s growth and the prioritization of such propaganda by President Xi Jinping.

Much of Beijing’s information warfare is used to discredit pro-independence views in Taiwan, advocate for the PRC’s model of governance, and encourage populist or forms of polarization. These actions increase political gridlock and undermine confidence in the democratic process in Taiwan and around the world.

This manipulation of Taiwan’s democratic and information space is a form of “sharp power,” and the CCP wields it to great effect. In Taiwan’s 2020 presidential campaign, for example, experts concluded that the unexpected popularity of the Beijing-friendly Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) candidate Han Kuo-yu was due partly to Han’s populist appeal in the poorer Taiwanese south, and partly to sustained online support—financed in large part by Beijing. Han’s support for the “one country, two systems” arrangement that Beijing has also forged with Hong Kong and Macao bolstered his popularity in the Chinese community prior to the election.

With Taiwan’s January election cycle in full swing, it is important to understand the primary actors in the PRC’s online influence operations and their methods. Taiwan can leverage its past, sophisticated approach to these operations to counteract PRC information operations—global civil society and governments can learn from Taiwan’s experience to do the same.

How does China seek to influence Taiwan’s elections?

Thanks to extensive linguistic and cultural ties, the information ecosystems of Taiwan and the PRC are closely intermeshed, allowing information to move back and forth across the Taiwan Strait with considerable ease. Doublethink Lab, a Taiwanese organization that studies the malign influence of digital authoritarianism, identified four PRC actors that operate at the forefront of Beijing’s efforts to weaponize information.

- State agencies and state-owned media;

- Provincial governments and social media platforms (e.g., WeChat or Weibo) controlled by Beijing;

- Commercial media, marketing, and public relations companies paid to circulate CCP propaganda;

- Social media and commercial content farms.

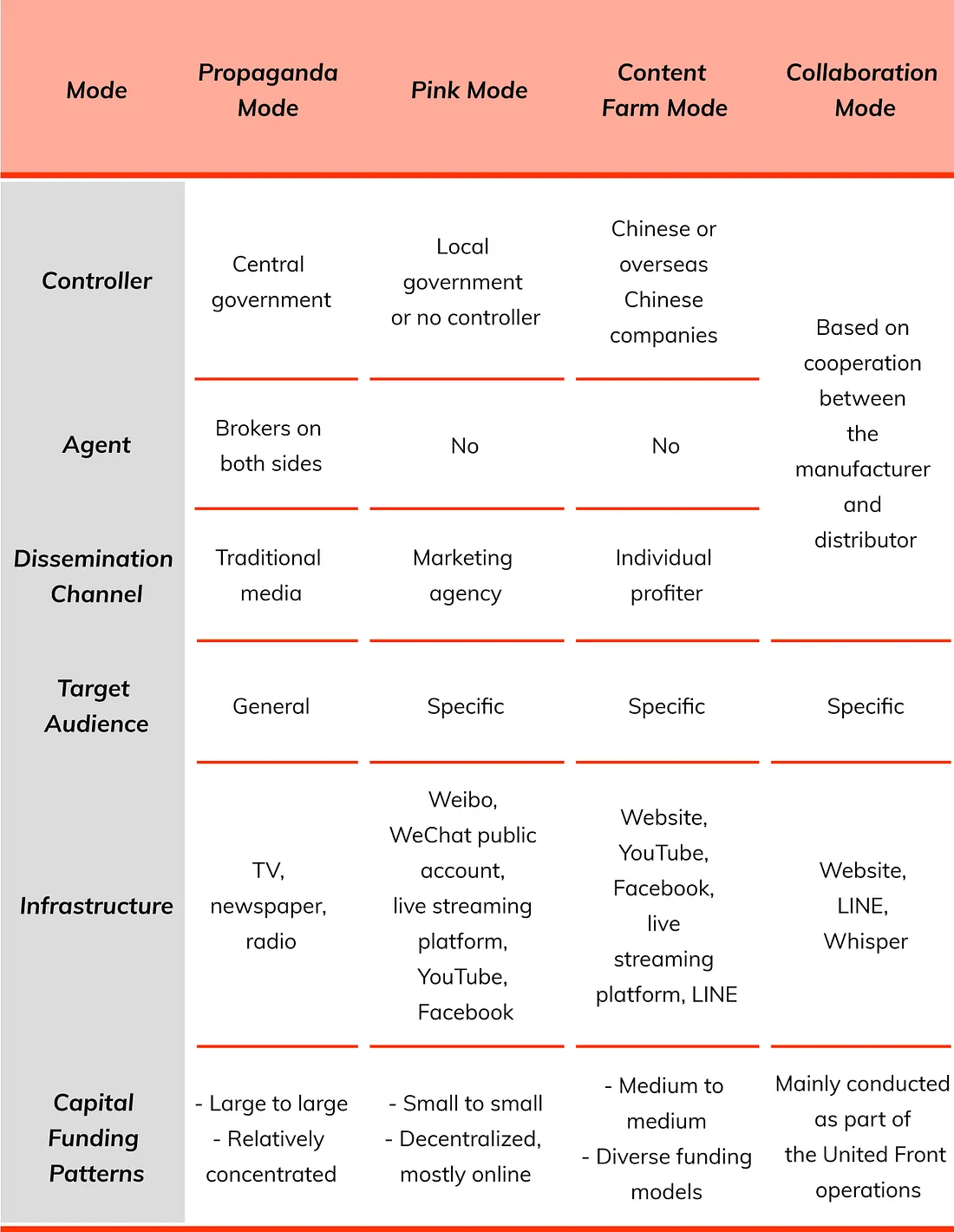

These actors operate in four ways.

- Agents of the central government disseminate disinformation and propaganda through traditional media channels;

- Local-level governments in the PRC do the same, albeit in a less-organized fashion;

- Social media influencers spread disinformation generated by CCP-backed content farms while linking this disinformation to local developments or grievances;

- Actors collaborate to distribute disinformation in a hybrid manner, often recruiting Taiwanese agents for influence operations originating on the mainland.

The four modes operation the PRC uses to influence Taiwan’s information space, as well as how these modes function.

The four modes operation the PRC uses to influence Taiwan’s information space, as well as how these modes function.

PRC operations in Taiwan range from coopting traditional religious groups or business associations to organizing cultural exchange activities, offering incentives in the tourism and entertainment industries, and influencing editorial content in media outlets with ties to business interests in mainland China. For example, in 2008, Taiwanese magnate Tsai Eng-meng, founder of a food manufacturing company with most of its market and production facilities in the PRC, purchased two television stations and a newspaper in Taiwan. All three media outlets became harsh critics of the current, Beijing-skeptic DPP government.

How has Taiwan responded to PRC information and influence operations?

Taiwanese civil society, technology firms, and government actors have not simply sat back in the face of these developments. Taiwan’s response to these operations has been sophisticated and multifaceted.

First, civil society groups, in particular fact-checking organizations, have played a vital role in countering PRC influence operations. In 2018, two non-profit organizations, Taiwan Media Watch and the Association for Quality Journalism established the Taiwan Fact Check Center to “curb the negative impact of false information and enhance the information literacy of the public to better foster the democratic development of Taiwan.”

Another fact-checking platform, Cofacts, was launched by g0v (pronounced “gov-zero”), a community of tech professionals who promote open government and participatory democracy. Cofacts uses crowd collaboration and chatbots to review information of unknown credibility. Volunteers analyze the objectivity and emotional pull of suspicious messages—elements that are difficult for AI to identify.

Second, other organizations like Fake News Cleaner focus on teaching information literacy, especially to older Taiwanese citizens. Fact-checking only goes so far in countering disinformation, and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to its negative effects. This generation will soon make up 20 percent of Taiwan’s population, and as relatively unsophisticated users of online tools, they have unwittingly become distributors of disinformation on social media. These false narratives have been especially popular on Line, the island’s most popular instant messaging app. Unlike other social media platforms, Line does not block falsehoods or cancel accounts that spread them. In 2019, however, the platform launched the Line Fact Checker app, outsourcing the job to fact-checking organizations like Fake News Cleaner and Cofacts.

Third, government authorities in Taiwan have become more vigilant in monitoring individuals vulnerable to PRC recruitment, from older military personnel who often side with their counterparts in the People’s Liberation Army, to businessmen whose mainland-based operations make them targets of PRC coercion.

Though identifying these risks is valuable, monitoring alone is insufficient, and democratic principles like free speech can actually limit the government’s ability to block false information. The previously cited case of Tsai Eng-meng is a good example. In 2020, after repeated warnings and fines, Taiwan’s National Communications Commission (NCC) declined to renew the broadcast license of one of Tsai’s media outlets, CTi News. Not only did the outlet skirt delicensing by continuing to air news on YouTube, but in May this year, the Taipei High Administrative Court overturned the NCC decision on the grounds that it was based on old criteria. Thus, the original NCC cancellation was deemed illegal and immediately revoked.

Fourth, Taiwanese media consumers have grown more patriotic over time and, therefore, resistant to CCP influence operations. With each new generation, more identify as Taiwanese, rather than Chinese. Thus, even when citizens encounter PRC disinformation, they read it with skepticism, if not outright hostility.

Finally, given the seriousness of the threat PRC-sourced disinformation poses to Taiwan’s internal stability, the government established a Ministry of Digital Affairs responsible for policy involving telecommunication, cybersecurity, the Internet, and communication industries. Beginning in 2022, the duties of Taiwan’s first Minister of Digital Affairs and successful software developer, Audrey Tang, has varied greatly and includes support for fact-checking and media literacy programs. However, the ministry’s most interesting work has been in designing digital platforms that address democratic weaknesses that are vulnerable to PRC exploitation and the pernicious effects of digital media generally.

Working with government policymakers, Tang and their ministry harness the power of social media while avoiding the divisiveness it triggers. For example, the ministry’s apps invite input on policy issues, while eliminating the “reply” capability and, with it, the spiraling rage fueled by the back-and-forth of commercial apps. The ministry also measures neither the opinions of respondents nor their understanding of the facts, instead gauging how users feel about certain topics. By measuring feeling rather than opinion, and by dropping a reply option that emotionalizes differences, Tang and the ministry seek to establish a “rough consensus” that officials can use to develop policies that provide solutions which enjoy broad, if imperfect, support.

When people have a voice in making public policy, Tang says, they are more willing to comply, even if they are skeptical to its effectiveness. By reducing internal divisions produced and politicized by social media, Taiwanese are also less likely to fall for their autocratic neighbor’s lies that seek to turn Taiwan’s elections into contests that produces winners and losers rather than a shared sense of collective achievement.

Taiwan’s efforts to counter Beijing’s aggressive use of information warfare should be of considerable interest to global democracies plagued by political polarization—especially that which is encouraged by internal or external malign actors. Scaling up fact-checking through AI and crowdsourcing, expanding information literacy—especially among older, less experienced users of social media—increased internal vigilance, and digital innovation within the democratic process itself have all proven to be useful tools at Taipei’s disposal. Other governments and civil society activists can do the same worldwide.

Ko Shu-ling worked as a journalist in Taiwan for 20 years and is a former Reagan-Fascell Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy. Follow her on Twitter: @KoShuling1.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. Image Credit: Andrii Yalanskyi/Shutterstock.