By Ryan Arick and Ariane Gottlieb

Over the past two and a half years, the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged societies and lives everywhere. Globally, the threat to democracy’s health has been comprehensive, too. Even as the pandemic potentially wanes, the crisis will continue to endanger democratic governance and offer authoritarian actors opportunities to expand their power. While democracy advocates devised innovative methods at the local level to push back, their responses to the erosion of norms have not sufficiently addressed this concerning trend. Democracy proponents everywhere must implement a stronger, coordinated response to blunt authoritarian political manipulation within their countries and across borders.

As the pandemic evolves, the International Forum for Democratic Studies will continue to monitor threats to democratic principles in our COVID-19 Analysis Hub. Though we will no longer publish the Pandemic Ploys newsletter regularly, we are pleased to announce that we will be launching Countering Kleptocracy, a monthly analysis on the impact of transnational kleptocracy and how democracies can respond. Subscribe here and stay tuned for more!

In covering these trends for the past two and half years, here is what we have learned…

The Pandemic’s Impact on Democratic Values

Authoritarian actors deployed propaganda, conspiracy theories, and dis- and malinformation campaigns to bolster their prestige, undercut criticism of their pandemic management, and discredit democracies’ health responses. The competition over ideas frequently played out amid the race to distribute medical supplies and vaccines. As the Forum’s research has shown, Moscow and Beijing have leveraged homegrown vaccines to cultivate positive perceptions worldwide and, at times, prioritize political objectives over public health concerns. These regimes have also disseminated fraudulent narratives about European- and U.S.-developed vaccines.

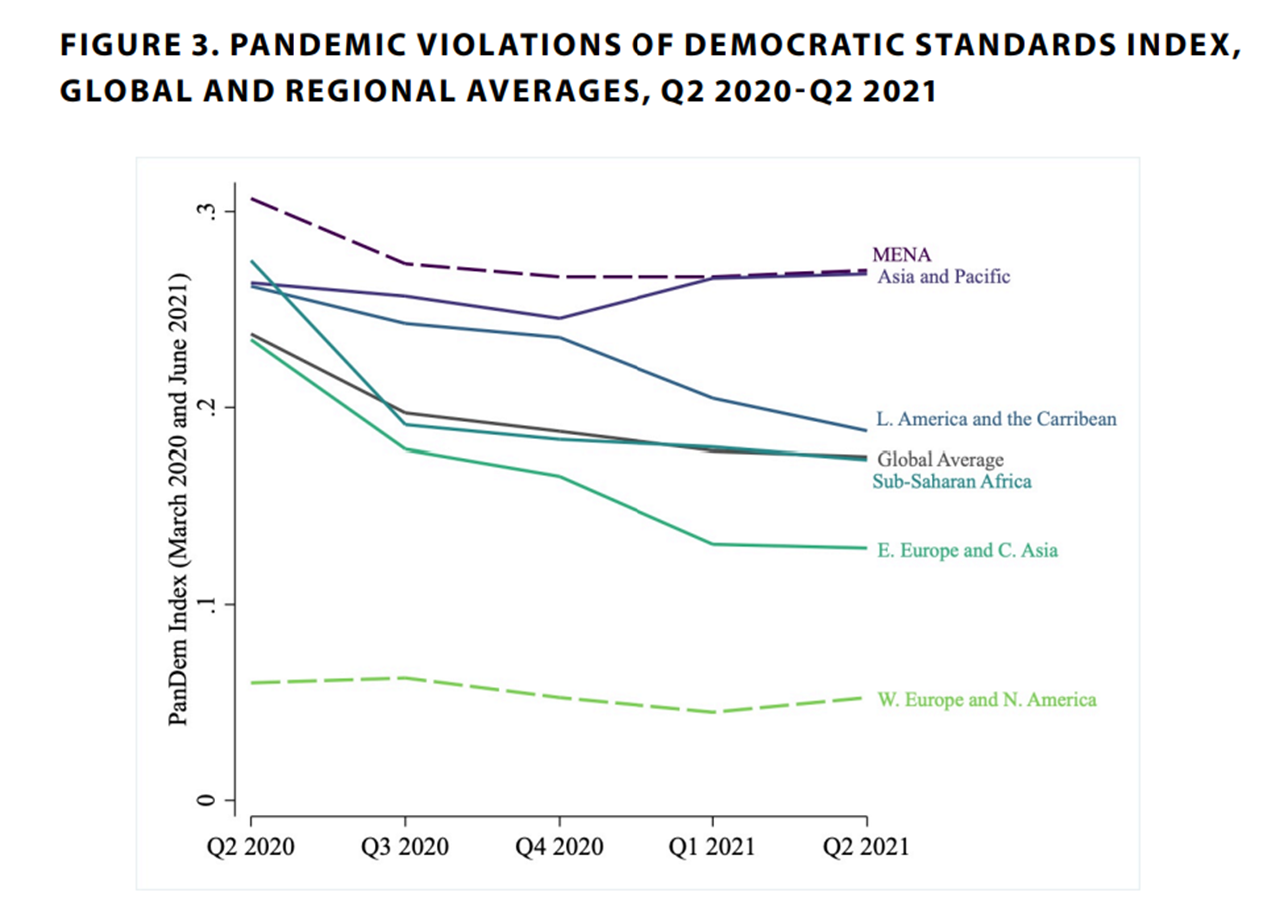

Pandemic-related democratic backsliding is a global phenomenon, with regions in the Global South experiencing a greater percentage decline in democratic standards than those in the Global North. (Chart reprinted with permission from V-Dem’s “Pandemic Backsliding” Policy Brief, accessible here.)

Government actors used the pandemic as a pretext to crack down on civil liberties and expand their power. Illiberal figures deployed a massive arsenal of political tools that enhanced opportunities for control over society. (For example, see the Forum’s Power 3.0 blog for insights into limits on free expression and illiberal electoral manipulation.) Such measures make an already tenuous climate for democracy and human rights activists worse.

Opportunities for corruption flourished during the COVID-19 pandemic, as government leaders took advantage of the rushed response to the virus to enrich themselves and their networks. Many leaders used the pandemic to relax public procurement procedures and weaken anticorruption bodies, while kleptocratic networks enriched leaders and their patronage networks with pandemic-related funds. Corruption scandals roiled powerful politicians who bypassed vulnerable populations to receive vaccines. Journalists and whistleblowers who exposed malpractice were harassed and intimidated for their reporting.

As countries pivoted to data-driven responses to the pandemic, many state actors seized the opportunity to expand their digital capabilities at the expense of human rights, privacy, and freedom. In many settings, contact tracing tools, exposure identification networks, and other technologies lack adequate transparency, privacy safeguards, and oversight mechanisms. Invasive tech, such as facial recognition systems, offered opportunities for authoritarian regimes to police COVID-related lockdowns and collect massive troves of data. Many countries weaponized regulatory measures introduced under the guise of combating “fake news” around COVID-19 to limit free expression online.

Resilience Strategies

While the challenges from the last two and a half years are significant, democracies and civil society stepped up. The many counterstrategies which emerged—civil society collaborations, digital activism, investigations, and political action from frontline defenders, and more—reflect strong democratic dynamism. However, this work is unfinished. Civil society, media organizations, democracy-assistance groups, and government actors can all play a role in countering these concerning trends.

Democratic governance models have been resilient in the face of authoritarian influence operations and autocratic temptations. While authoritarian actors relied on propaganda, conspiracy theories, and disinformation to highlight their purportedly superior pandemic responses, democracies such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Australia demonstrated that proportionate health measures can be consistent with democratic ideals. Additionally, the 2021 Summit for Democracy brought together stakeholders to conceptualize how to build resilience and institutional trust, prioritizing clear communication, accountability, and equity. These models were juxtaposed by China’s Zero-COVID strategy which demolished individual liberties in some Chinese cities. (For deeper analysis of how states fostered opportunities for democratic rejuvenation, see “A Light in the Dark” from the Power 3.0 blog.)

Additional funding and resources helped local outlets survive the challenging economic landscape and counteract the spread of disinformation. The pandemic dealt a severe blow to critical revenue streams for independent media. External stakeholders, however, enabled journalists to provide accurate information and fact checks within their communities. In Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, an uptick in grants provided critical assistance for a number of digital native media outlets. These outlets punch above their weight relative to larger media organizations, with many producing cutting-edge investigative or data-driven journalism. Meanwhile, UNESCO’s Multi-Donor Programme for Freedom of Expression and Safety of Journalists provided training and facilitated conversations among local media figures on best practices for reporting on the pandemic, countering disinformation, and safeguarding free expression.

In the face of many barriers to public advocacy, protestors, civil society groups, and others devised innovative methods to push back against repression and provide support to their communities. Such adaptations by civil society run far and wide. Netizens in China created a virtual “Wailing Wall” to memorialize a doctor whom the Chinese Communist Party tried to silence. Democracy activists in Hong Kong turned to preexisting networks to distribute PPE and used social media to remind citizens to abide by public health measures. Chilean protestors projected images of mass demonstrations in public spaces in lieu of in-person gatherings and called for change from the safety of their balconies.

Despite widespread opportunities for corruption and increased intimidation, civil society groups, journalists, and activists investigated illicit financial flows through globally connected, collaborative investigative networks. Investigative journalism continued to hold governments accountable. Media organizations and journalists launched efforts to track and expose corruption during the pandemic. Crowdsourced tips and stories proliferated as citizens documented their everyday experiences with governmental overreach and misuse of resources. Collaboratives like Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists shifted attention from long-form analysis to daily exposés shining a spotlight on corruption and failed political responses to the pandemic. African civil society groups, including Gambia Participates, Nigeria’s International Centre for Investigative Reporting, and South Africa’s C19 People’s Coalition tracked mismanagement of relief resources. Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia mirrored these practices.

Civil society groups have illuminated how authoritarian and illiberal leaders used emerging technology to serve their own interests. Although other nations often neglected to include digital protections for ordinary citizens in their public health surveillance tools, civil society honed its ability to recognize and fight back against unlawful government encroachment in the digital sphere. Watchdog organizations and activists in Russia drew attention to the sweeping network of facial recognition tools and the lack of protections for data privacy. In Latin America, the Al Sur NGO consortium called for several facial recognition systems across the region to include transparency mechanisms. Additionally, some states such as Taiwan implemented relatively rights-respecting digital strategies to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

Looking Forward

While many people believe their countries and communities are coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus has other ideas. Likewise, authoritarians are not abandoning their tried and tested strategy of leveraging the crisis to enhance their power. Civil society and other democratic actors must keep pace with ongoing democratic erosion at the international level. Relative to the scope and magnitude of current challenges, civil society responses have been localized and small. The multilateral community has largely failed to operationalize such countermeasures at scale or hold state actors accountable, enabling malign figures to embed illiberal norms and practices within domestic and global contexts. Thus, the international democratic community—in consultation with voices from across civil society—must pursue a coordinated and comprehensive effort that can be deployed across borders, sectors, and regime types.

Response strategies include:

- Solidify democratic norms as an ideological cornerstone within multilateral organizations and cultivate global coalitions.

- Provide support for media actors, NGOs, and civil society. Efforts to bolster local media and civil society should cultivate learning; emphasize digital literacy; and support creative adaptations amid ongoing threats.

- Strengthen support for investigative journalists and whistleblowers to uncover the malicious use of technology to target human rights activists, opposition politicians, and journalists as well as the misuse of COVID-related funds.

- Facilitate opportunities for networking, collaboration, and knowledge-sharing among civil society to develop and communicate best practices and innovative methods.

- Establish benchmarks which safeguard human rights, freedom of the press, and the rule of law.

- Counteract illicit financial flows through increased transparency in the banking and real estate sectors, and support enforcement and watchdog institutions.

- Adopt stringent legal countermeasures to counteract digital authoritarianism, such as privacy safeguards and transparency protocols, while promoting a more pluralistic and rights-respecting tech realm.

- Restrict public health surveillance technologies to maintain a proportionate level of restraint, continued oversight, and a commitment to transparency.

While civil society adapts to these ongoing challenges to democracy, it must also recognize the vulnerabilities the pandemic exacerbated and work to mitigate the persistent threats from authoritarian and illiberal actors. Civil society activism should complement international coalitions and collaborative networks to strengthen the international commitment to democratic principles. After two and a half years (and counting) of the public health crisis, civil society and democracies have an immense opportunity to address the ongoing danger to both public health and global governance.

Ryan Arick is an assistant program officer at the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies. Follow him on Twitter @Ryan_Arick.

Ariane Gottlieb is a program assistant at the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. Image Credit: ETAJOE/Shutterstock.com