By Claudia Flores-Saviaga and Deyra Guerrero

At the Ninth Summit of the Americas (June 6-10, 2022), U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken highlighted the fundamental challenges from “disinformation from government and non-state actors” in Latin America’s information ecosystem. Blinken and other summit participants also warned of an upsurge in disinformation across Latin America and pledged to keep fighting it. Observers have long acknowledged that authoritarian regimes use disinformation as “weapons of war.” These threats are now even clearer in focus, as the Kremlin is attempting to influence the media around the world with a series of false narratives regarding its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. This flood of disinformation—in various formats—is particularly acute in Latin America.

Our recent research shows that Russian state-backed media outlets present on Latin American social media channels, such as Actualidad RT and Sputnik, along with Russian embassies and consulates, spread disinformation about the country’s invasion of Ukraine. A recent study showed how Russian diplomatic accounts amplified falsehoods by Actualidad RT and Sputnik News about Ukrainian bioweapons, false justifications for Russia’s invasion, and NATO. Unfortunately, Russia’s disinformation in Latin America is not new, and regional fact-checking organizations and innovative cross-regional collaborations face both successes and challenges in trying to keep pace with Russia’s disinformation.

Analyzing Regional Engagement with Russia’s Disinformation about Ukraine

Moscow has expanded its influence in Latin America through arms sales, commercial agreements, high-level political outreach, and disseminating Kremlin-backed disinformation. However, little is known about how audiences engage with these narratives, such as those about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To better understand this issue, we tracked Russian embassy and consulate Facebook accounts in Latin America—as well as those of Sputnik News and RT in Spanish. We focused our research on Facebook posts about the invasion, as Facebook is the most popular social media network in Latin America. We used CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Meta, to gather data from February 24, 2022 (the start of Russia’s expanded invasion) until May 12, 2022, analyzing 2,592 posts about the war that these accounts shared.

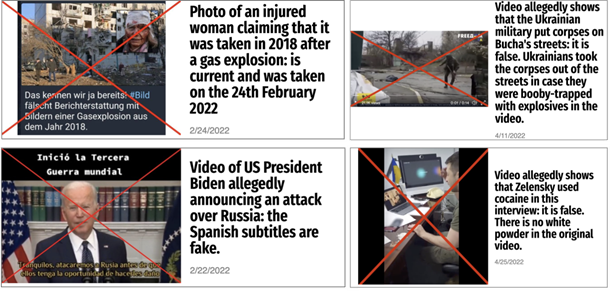

Fig 1. Examples of disinformation about Ukraine that circulated on Facebook in Latin America. (Images taken from ukrainefacts.org).

For this study, we analyzed positive reactions (“love” and “care” emojis) and negative reactions ( “angry” and “sad” emojis). We disregarded the “like” reaction from our analysis as previous research showed it lacked any correlation with a clearly positive or negative emotional expression. Also, our study did not take into consideration whether these interactions originated from inauthentic accounts, and we acknowledge that this decision may influence our investigation’s results.

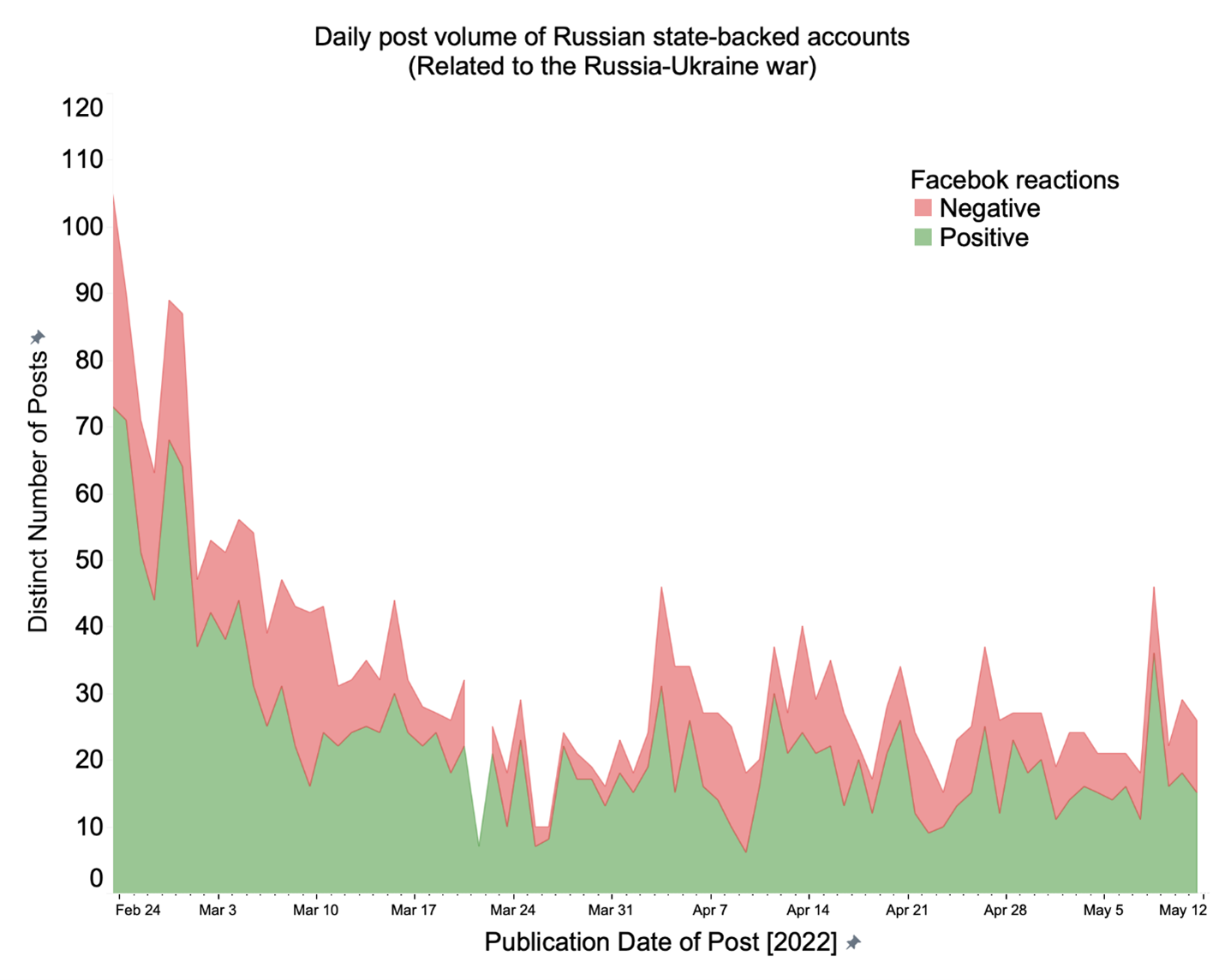

Our research revealed that Russian state media posts have received high user engagement and positive reactions throughout the conflict, especially at the beginning of the invasion. Figure 2’s x-axis represents the date on which the post from Russian state-backed accounts was published, and the y-axis represents the total number of posts published on a given day. The green segments show the number of posts that received more positive than negative reactions while the red segments measure the opposite.

Fig 2. Daily posts figures from February 24, 2022 (the start of the war) until May 12, 2022, of Russian state-backed accounts, colored by positive (green) and negative (red) reactions. (Authors’ research)

For example, on February 24, Russian state-backed accounts released 108 posts, 59 of which received more positive than negative reactions that day. The other 49 posts received more negative reactions. (The post that received the highest user-engagement—positive and negative—on that day is a video that shows Putin calling on the Ukrainian Army to immediately lay down their arms and return home to their families.)

In another notable post released on Russia’s Victory Day (May 9, 2022), Vladimir Putin falsely claimed that NATO countries refused to sign a security guarantee agreement with Russia and instead prepared to invade, forcing him to respond. The post received 642 positive reactions and 15 negative reactions.

For the period studied, the posts we analyzed largely received more positive than negative reactions (96 positive reactions vs. 41 negative reactions on average). Additionally, though most posts were generated at the beginning of the war, they have been released at regular intervals. Russia’s efforts to spread their preferred narratives in Latin America have had a demonstrable effect on official Latin American responses to the invasion. For instance, on March 2, 2022, though the UN General Assembly voted to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and demand a withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory, Cuba, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and El Salvador abstained from voting. Furthermore, Mexico and Brazil declined to impose economic sanctions on Russia.

Undoubtedly, the Kremlin has an active and pervasive presence in Latin America’s information ecosystem, but how has regional civil society responded to the spread of Russia’s disinformation narratives?

Activating Fact-Checking Collaborations within Latin America and Across the Globe

Numerous fact-checking organizations have been established across Latin America to combat disinformation, including Kremlin-backed information operations. There are currently, by the authors’ count, thirteen media outlets exclusively dedicated to fact-checking in the region. Chequeado in Argentina, established in 2010, was among the first of these organizations. Similar initiatives have since been founded in Uruguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela, and Bolivia—multiple organizations also operate in other countries. Also, at least 24 fact checking teams now exist within broader media organizations in Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Notably, Mexico’s Verificado 2018 initiative brought together over sixty media organizations to verify major candidates’ statements during the nation’s elections that year. The initiative has since been replicated in other countries. Organizations such as VerificadoMX work closely with traditional media and print media and offer free media literacy workshops to help journalists develop their fact-checking skills.

To further consolidate and strengthen regional fact-checking activities, LatamChequea, a consortium of more than thirty organizations in 21 countries, was established in 2014. Through this network, fact-checkers share information and publish their findings on various news items across Latin America. LatamChequea also works with the International Fact-checking Network to verify topics of international relevance, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Currently, LatamChequea is combating disinformation about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine through the #UkraineFacts initiative, a collaborative database documenting disinformation narratives about the war worldwide. The database emerged after the realization that several fact-checkers in Europe were verifying the exact same content about the conflict, which allowed Latin American fact-checkers to more easily target their own efforts. This collaborative database has helped fact-checkers in Latin America develop digital materials to debunk Ukraine-related disinformation, share this data with other fact-checkers, and avoid duplicating other organizations’ efforts.

In line with these efforts, researchers and activists consider audience participation as essential to help counter disinformation. As such, various methods are employed to foster closer relationships with citizens. For example, VerificadoMx has created WhatsApp and Telegram groups devoted exclusively to providing fact-checking information about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine directly to readers. By using these channels—among others—the public can participate in this effort as equal collaborators and help provide materials to help debunk false narratives.

The Challenges to Countering Russia’s Disinformation in Latin America

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine presents new challenges to regional fact-checking initiatives. First, many pro-Kremlin groups have also been established on numerous closed chat platforms, specifically Telegram. Though citizen fact-checking networks can operate on these web-based chat apps to great effect, so, too, can Kremlin-backed disinformation campaigns, complicating content moderation efforts. Moreover, while citizen initiatives offer an exciting opportunity to combat regionally-focused disinformation in real-time, this strategy is hard to implement at scale—especially since citizens might not be aware of these groups’ existence. And for organizations that are widely known, the challenges that the lack of human resources present remain difficult to overcome.

Indeed, many Latin American fact-checking organizations struggle to identify and analyze the mass amount of disinformation spreading in the region. These organizations are simply overworked. In addition to debunking new false information about Ukraine, these groups still work to combat long-standing false narratives about the COVID-19 pandemic and other topics. They are hamstrung by limited resources (human, material, economic, etc.) and forced to shift their labor and focus constantly as a consequence. Thus, regional fact-checking organizations often overlook important local and national issues in order to prioritize topics of broader global importance, undermining their ability to counter localized disinformation, like during local elections.

Furthermore, social media content moderation resources are primarily designed to tackle English language content. There are only a few resources that counter disinformation in Spanish or other languages. Some platforms, like Facebook, are making progress by strengthening their partnerships with Latin American fact-checking organizations. Nonetheless, researchers are concerned that tools like CrowdTangle may be discontinued, as widely reported. Easy-to-use tools like CrowdTangle are indispensable in analyzing disinformation and play a key role in encouraging social media platforms to increase their transparency regarding content moderation and anti-disinformation efforts. Better access to this information would allow researchers and activists to create informed, vital solutions to counter disinformation worldwide more easily. In the absence of disinformation data, researchers are frequently forced to collect relevant data as quickly as possible before it is permanently deleted or destroyed.

Implications

It is difficult to measure the success of recent and long-term fact-checking initiatives in Latin America, even more so in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Disinformation in the region is pervasive, and prevailing mistrust of the media and journalists as well as low-quality information and low media literacy makes this work incredibly challenging. In fact, many in Latin America seem sympathetic to these Kremlin-backed narratives.

To overcome this problem, it is crucial to prioritize collaborative work as a way to monitor more topics, identify and counter disinformation more quickly, and maintain access to disinformation data to better implement counter-disinformation strategies.

The counter-disinformation community must nurture greater awareness of disinformation among communities across Latin America. Regional fact-checking organizations have championed several initiatives designed to tackle this issue in recent months. On April 2, 2022, the Latin American Network of trainers in fact-checking was announced, promising to train journalists and university professors from Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, and Peru in identifying and combating disinformation more effectively. Ideally, those who participate can train others to conduct this work, including the public.

New initiatives, such as the Google News Initiative, can also help fact-checking organizations diversify their business models. The recently announced hub of the Digital Communication Network of the Americas that has established networks of journalists to share tools and strategies to counter disinformation is an important example of how we can better support regional fact-checking organizations. Increased investment from technology companies to help fund new, often understaffed and underfunded projects, like VerificadoMX and Serendipia’s Temoa, would also be effective.

Finally, it is essential to encourage state and private educational actors to work together to develop media literacy tools and programs in support of these counter-disinformation efforts. Although media literacy programs have been in development for nearly five decades, they have not translated into sustained public policies. Regional researchers must be supported to develop technology specifically for the region to combat disinformation and uphold the integrity of Latin America’s information ecosystem.

Claudia Flores-Saviaga is a Computer Science Ph.D. candidate at Northeastern University and member of the Information Operations research group at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. She studies disinformation campaigns and designs large-scale solutions for Latinx communities in partnership with governments, industry, and universities in Latin America and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @saviaga.

Deyra Guerrero is a university professor, journalist, and co-founder of VerificadoMX, a fact-checking organization in Mexico. Currently, she is completing her Ph.D. in Journalism at the Complutense University of Madrid. Follow her on Twitter: @crononautamx.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. Image Credit: Misha Friedman/Getty Images