By Ariane Gottlieb

Election day evokes images of crowded rallies, stirring speeches in packed venues, and lines of voters that stretch around the block. It also recalls the active debates and civic engagement that are hallmarks of participatory democracy—voting is both a physical and social activity. Yet over the last year and a half, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted unprecedented public health measures and disrupted many facets of daily life, elections among them.

Illiberal political leaders have exploited this crisis and manipulated the playing field to their advantage. In some countries, measures designed to preserve public health and safety have been used to alter scheduled election cycles, stifle civic participation and campaign activities, and limit opportunities for independent election observation. This variant of electoral repression entrenches autocratic norms within state and civic institutions. Moreover, complacency in democratic societies toward the global proliferation of COVID-era threats to political rights could enable a gradual slide towards authoritarian tendencies, even once the pandemic eventually wanes.

Measures designed to preserve public health and safety have been used to alter scheduled election cycles, stifle civic participation and campaign activities, and limit opportunities for independent election observation.

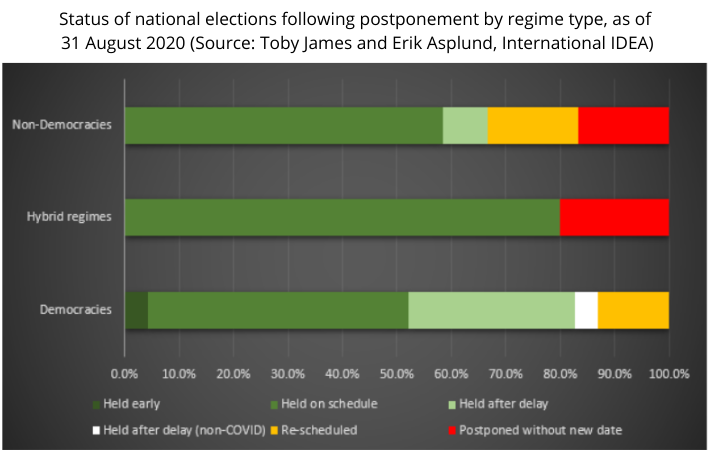

According to a briefing by the European Parliamentary Research Service, election deferral is not necessarily synonymous with repression, provided that enacted measures balance democratic norms and safety concerns. In fact, many countries amended election calendars due to public health concerns, either postponing or rescheduling national or regional elections. Furthermore, as a study by International IDEA determined, democratic states that postponed elections due to COVID-related concerns were more likely than hybrid or nondemocratic regimes to establish a new date.

Some leaders within illiberal regimes, however, manipulated election calendars to advantage a preferred candidate or stifle political participation under the pretext of safeguarding public health. According to data from International IDEA displayed in the below chart, multiple hybrid and nondemocratic regimes exploited pandemic response measures to postpone elections, sometimes indefinitely. Electoral delays can allow such leaders to alter the timing of elections in favor of a certain candidate—often themselves—and to take advantage of other political considerations, like approval ratings. The manipulation of public health measures in this manner threatens democratic norms and practices.

The assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse exemplifies this dangerous dynamic. The island nation has long suffered from political instability, and President Moïse—who took office in 2017—ruled by decree during his last year in office and took steps to centralize his power. A controversial constitutional referendum was to be held, yet the referendum—along with local elections—was postponed, initially without a new date set and purportedly because of COVID-19. This delay unfolded amid a broad political crisis in Haiti which culminated in Moïse’s July 7th assassination. Now, Haitian democracy hangs in the balance.

Likewise, hurried elections can also be damaging to democracy. In Serbia, opposition figures accused state officials of rescheduling a postponed parliamentary election too soon, with some speculating that the government rolled back a wide array of public health measures so that the election could proceed earlier than anticipated. This decision led some analysts to conclude that President Aleksandar Vučić—whose approval ratings were in decline—sought to hold the election as quickly as possible to take advantage of the political landscape and escape voter punishment at the ballot box.

Illiberal regimes also exploited emergency powers and responses. Nominally invoked to reduce the pace at which the pandemic worsened, these mandates allowed a number of leaders to stifle civic engagement and suppress democratic participation. For example, Hungary’s parliament passed legislation that, among other measures, suspended elections and allowed Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to rule by decree. While this state of emergency was subsequently lifted, the government later implemented similar measures establishing emergency powers with a ninety-day time limit. Among a number of other factors, Orbán’s expansion of powers during the pandemic has contributed to democratic decay in Hungary.

Leaders also weaponized social distancing measures to stifle free expression and association. Such measures undermined the ability of political opponents to challenge incumbents at the ballot box. In November 2020, for instance, Ugandan authorities arrested presidential opposition candidate Bobi Wine for allegedly defying COVID-era regulations on campaign events. Wine was later subjected to a de facto house arrest without criminal charges. Wine’s arrest, as well as other measures that stifled free expression for media and opposition figures, were enacted under the guise of mitigating the virus’ spread. Furthermore, when safety concerns prompt campaigns to scale back in-person events, the cooptation or suppression of independent media often amplifies incumbents’ influence over election-related narratives. As such, crackdowns on free expression—which the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated—can have an even more chilling effect than in the pre-pandemic era.

When safety concerns prompt campaigns to scale back in-person events, the cooptation or suppression of independent media often amplifies incumbents’ influence over election-related narratives.

Finally, illiberal regimes have taken advantage of pandemic travel restrictions to limit independent electoral observation. International Election Observation Missions canceled multiple missions in 2020 due to health concerns, travel restrictions, or quarantine requirements. Although observation missions adopted novel strategies to safely conduct their work—including partnering with domestic observers and operating virtually—some leaders seized these opportunities to hold elections without independent forms of oversight. In Burundi, for example, despite relatively few social distancing requirements on the citizenry, the government imposed a quarantine on foreign observers, precluding election observation. Law enforcement also arrested over 200 observers from the opposition’s political party. By exploiting restrictions on assembly and mobility, illiberal regimes were able to suppress a critical mechanism for democratic accountability and participation.

Considered in isolation, the pandemic adversely impacted elections in many settings around the world. The exploitation of pandemic responses and public health initiatives, however, paint a worrisome picture for democratic stability, should restrictive pandemic-era measures remain in place after the crisis ends or due to potential knock-on effects on democratic norms and practices in the long term. Though these trends are troubling, democracies have the tools required to combat this threat. Political leaders should ensure that changes to electoral processes are enacted in accordance with national and international law and receive support from diverse political coalitions. Moreover, COVID-era policy responses must be proportional, nondiscriminatory, terminable, and narrowly tailored. Civil society organizations can encourage electoral management bodies to enact short-term policies or reforms that encourage accessibility and accountability of democratic processes; support election observation missions amid restrictions on movement; and ensure a robust information space. Despite the ongoing challenges that the pandemic poses, democracies must counter these threats to their norms and institutions and maintain fair and open elections as a bulwark of democratic governance.

Ariane Gottlieb is a program assistant at the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Image Credit: Ruslan Grumble / Shutterstock.com