By Alexander Dukalskis

Before he boarded his flight from Athens to Vilnius on May 23, dissident Belarusian activist-journalist Raman Pratasevich expressed concern that Belarusian security services had followed him in the airport prior to his flight and even attempted to photograph his travel documents. His fears were realized a few hours later. Belarusian authorities forced Pratasevich’s RyanAir flight to land in Minsk before it left Belarusian airspace and pulled him off the flight. As of this writing, he is in police custody, where he faces years in jail, perhaps even the death penalty. He was forced to give a televised “confession.” Pratasevich’s girlfriend Sofia Sapega, a Russian national, was also removed from the flight and remains in pre-trial custody.

This audacious act grabbed the world’s attention. Why would Alyaksandr Lukashenka, Belarus’ authoritarian leader in power since 1994, care about a 26-year-old blogger living abroad and potentially risk so much to silence him? The answer is both straightforward and mind-boggling: Pratasevich, a fierce critic of Lukashenka, published information that was damaging to the dictator’s power and reputation—both domestically and internationally.

Although Pratasevich’s abduction was dramatic, this kind of “transnational repression” happens with grim regularity. For my new book Making the World Safe for Dictatorship, I gathered information on all publicly documented instances in which authoritarian governments targeted their own citizens abroad with threats or physical coercion.

The numbers are bleak. Using only open-source information, the book documents nearly 1,200 events involving more than 2,500 victims (some events targeted more than one person at once) between 1991 and 2019. Given that transnational repression is usually designed to be secret or otherwise goes unreported, this figure likely underestimates the true scale of transnational authoritarian repression.

This compiled data, available in the Authoritarian Actions Abroad Database, shows how authoritarian states target dissidents who have sought refuge overseas. Criticism by citizens exiled from authoritarian settings carry weight that is born of experience. The authority with which such dissenting voices speak places them at particular risk of repression from ever more internationally active autocrats. Examples such as Saudi Arabia’s Rapid Intervention Force silencing all forms of dissent, Chinese authorities threatening Uyghurs abroad via WeChat, and Rwandan intelligence officers assassinating Paul Kagame’s critics abroad illustrate the pervasiveness of transnational repression. Fundamentally, this practice is an outward projection of an authoritarian regime’s efforts to control the public sphere and an extension of their repressive capacity at home. As authoritarians consolidate power and suppress dissent, opposition actors are driven abroad. Consequently, they view these exiled critics as transnational threats.

Most targets of authoritarian transnational repression do not represent immediate or serious threats to the power of dictators. Their offense, in simple terms, is that they have shared information that makes the government look bad. Whether it is about internal repression, corruption, or something else entirely, their criticisms—or simply their identity as a defector, as in the case of North Koreans who have fled the country—undermine the dictators’ efforts to build and project a positive image for foreigners.

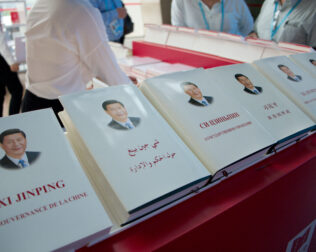

This issue illustrates the fundamental point at the heart of my book: autocracies do not simply try to promote a positive image of themselves abroad, they also work to silence critics and criticisms wherever they occur, including beyond their own borders. Just like propaganda and censorship have a symbiotic relationship, so do “promotional” and “obstructive” forms of authoritarian image management. Dictatorships promote a positive image of themselves through promotional tactics, like conducting external propaganda campaigns or harnessing the transnational reach of public relations firms. They also use obstructive tactics to discredit opponents and stifle dissent. The strategy is often built on a foundation of denying access to information about what happens domestically, as when China’s authorities restrict the foreign press or when authoritarian states prevent academic fieldwork or archival research.

Of course, authoritarian image management tactics do not always work, and sometimes authoritarians’ obstructive actions may even undermine their promotional objectives. Indeed, Lukashenka’s proxies face an uphill battle to deal with the international fallout from the Pratasevich-Sapega arrests.

Ultimately, the practical tools to influence Lukashenka are limited, and he may have calculated that silencing a critic was worth the consequences. Weak responses to previous crackdowns in Belarus and elsewhere may embolden autocrats like Lukashenka. The international community’s attention span is often short. Belarus may be out of the headlines soon and, in detention, Pratasevich will no longer be able to amplify information critical of the government. For every Pratasevich who makes global headlines there are dozens of repressed exiled critics around the world who remain largely unknown. But this does not have to be the case. The global community of democracies will need to be as purposeful on behalf of freedom of expression as the Belarusian authorities are in trying to smother it.

How should democracies respond to this challenge? On transnational repression specifically, Freedom House has proffered many policy recommendations built around law enforcement training and more supportive refugee policies. Greater transparency should be encouraged around affiliations between authoritarian governments and lobbying groups, or with authoritarian state media outlets like RT and China Global Television Network (CGTN). Also, in the higher education sector, a recent National Endowment for Democracy working paper outlines recommendations to avoid authoritarian and kleptocratic reputation laundering through universities—a central means by which authoritarians promote their image.

In this new and challenging environment, democracies should play to their strengths. They should harness the tools and advantages that are inherent to them: the transparent exchange of ideas and the freedom to express them. Transparency should be prioritized over censorship, and the value of the free press should be celebrated, not denigrated. Championing democratic values at home, even when under difficult circumstances, is vital. The promotion of democratic norms and values is the most effective antidote to authoritarian image management and transnational repression.

Alexander Dukalskis is an associate professor at University College Dublin in the School of Politics and International Relations. His most recent book is Making the World Safe for Dictatorship. Follow him on Twitter @AlexDukalskis.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Image Credit: Andrey_Popov / Shutterstock.com