By Allison McManus

In April 2019, Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouli and Information Minister Amr Taalat met with Li Jie, chairman of the supervisory board of Chinese telecom firm Huawei, to discuss cooperation in the technology sector. Afterward, headlines announced that Huawei would experiment with a 5G rollout during the African Cup of Nations (AFCON) tournament in Cairo the following June. The Prime Minister lauded the deal, though some raised concerns about partnering with the Chinese tech giant (which has faced intense scrutiny over data sensitivity and its perceived ties to the Chinese Communist Party).

The heavily publicized announcement never materialized into an actual 5G network at AFCON, or since; no further announcements were made about a launch, and no attendees reported utilizing the network. While the news may not have had material significance, it serves as a metaphor for the Sino-Egyptian relationship in the technology sector: much fanfare about the economic boons of partnership, but with little clarity around outcomes or the repercussions for human rights and freedoms.

Since Beijing announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—its plan to create strategic infrastructure connecting Africa, Europe, and Asia to China—in 2013, Egypt has become a key area of investment. By 2012, China had already surpassed the United States as the primary exporter of goods to Egypt, and in 2014 Egypt and China signed a “comprehensive strategic partnership” agreement. This blooming relationship comes at an opportune moment for Cairo, which hopes to woo foreign investors into an economy that in 2016 reached the brink of crisis. News of Chinese trade and investment has surged since 2014; in October 2018, the Financial Times reported a healthy $24.3 billion USD in cumulative Chinese investments in the country.

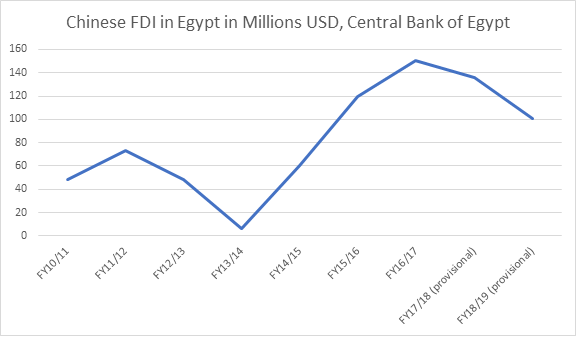

However, like the 5G rollout at AFCON, many of these announced projects never materialized. Of the amount trumpeted in late 2018, $20 billion disappeared after talks on construction of Egypt’s New Administrative Capital fell through. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) that year actually came in closer to $100 million. (According to reports from Egypt’s Central Bank, China remains Egypt’s largest creditor outside of international financial institutions, with Egypt’s national debt approaching unsustainability).

Though infrastructure and construction are major areas of investment, telecommunications is another area where China has made inroads into Egypt. Beyond the 5G AFCON announcement, China has financed Egypt’s telecoms sector and, according to a researcher with Egypt’s Foreign Trade and Industry Ministry, the 82 Chinese telecoms firms operating in Egypt as of 2019 represent $14 million USD in FDI.

While some projects have fizzled, Cairo has a demonstrated appetite for investment in telecommunications and surveillance technology which foreign companies have been happy to feed. Huawei has maintained an “OpenLab” for tech collaboration in Cairo since December 2017, and in June 2019 Egpyt’s Minister of Higher Education met with Huawei representatives to discuss the development of “smart” technology in the Egyptian university system. According to a February 2019 agreement, Huawei is projected to debut North Africa’s first cloud computing network in Egypt during the first quarter of 2020; the Chinese firm Hikvision is already providing CCTV cameras for buses in Egypt’s Suez governorate. International firms such as Honeywell and Etisalat Misr (a local subsidiary of the Emirati giant) have also announced memorandums of understanding to support smart city technology in the new capital.

While these developments support Cairo’s portrayal of Egypt as a modernizing Arab economy, persistent shortcomings remain. Shortages in funding and skilled labor and the market dominance of inefficient military-owned companies are just two pitfalls for ambitious projects in Egypt.

These shortcomings aside, continuing Egyptian demand and Chinese firms’ growing exports make the possibility of deeper Sino-Egyptian cooperation worrisome. Privacy rights watchdogs have criticized Egypt for its surveillance of activists, dissidents, and other citizens, and legislative changes have weakened protections for privacy and free expression. Were they introduced to Egypt, China’s advances in areas like facial recognition would likely accelerate these trends and could give China access to sensitive data (as they have in countries like Zimbabwe).

For its part, Cairo has helped identify and detain Uighur Chinese citizens in Egypt for interrogation and repatriation to China, where they may face enrollment into brutal “re-education” facilities likened to concentration camps. Egypt has allowed Chinese officials to interrogate Uighurs in Egyptian prisons, a rare exception to usual Egyptian practice. These efforts come at the same time as public displays of friendship between Egyptian and Chinese officials, with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi having made six visits to China since taking office.

A cozier security and political relationship belies any sense that Chinese investment in Egypt will remain purely economic. While many unknowns remain about the extent of Chinese involvement and Egyptian capacity in sensitive sectors like technology, stronger bilateral relations between the two authoritarian governments seem likely to pose serious repercussions for democracy and human rights in the foreseeable future.

Allison McManus is a non-resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for for Middle East Policy, where she was previously research director. She holds an MA in global and international studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara. You can follow her on Twitter @AllisonLMcManus.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Image credit: Gabi Luka / Shutterstock.com