By Laura Rosenberger

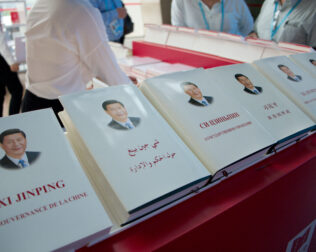

There is little debate today that authoritarian powers are using asymmetric tools to weaken democratic institutions in other countries. Extensive work has documented and exposed Russia’s efforts to interfere in and undermine democracies across the trans-Atlantic space, and the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to subvert democracy and covertly influence debate in the Asia-Pacific, and, increasingly, other regions. These operations employ a combination of tactics, including information operations, cyberattacks, malign financial influence, strategic economic coercion, and subversion of civil society.

But democracies have been slow to acknowledge this threat—and even slower to devise effective solutions. Several factors complicate democracies’ efforts to mount effective responses to interference operations. First, foreign interference operations often target sensitive domestic political issues and processes, including elections, and exploit existing weaknesses within democratic societies. Second, these operations often turn democracies’ greatest strengths—openness, innovation, robust debate, interconnectedness—against them. Third, authoritarian powers are defining the battlefield in ways advantageous to them—meaning that symmetric responses are often more difficult or less effective for democracies to undertake, in some cases because responding in kind would be inconsistent with democratic values. Fourth, interference operations often use clandestine and plausibly deniable tactics, complicating attribution and response. Finally, the tactics of foreign interference operations often fall in bureaucratic seams, limiting democracies’ ability to see the whole threat picture or respond across all available tools.

Authoritarian powers are defining the battlefield in ways advantageous to them—meaning that symmetric responses are often more difficult or less effective for democracies to undertake, in some cases because responding in kind would be inconsistent with democratic values.

These challenges are not insurmountable, but they will require dedicated effort from governments, the private sector, and civil society to address these threats with a whole-of-society strategy. That strategy must include defensive measures designed to close vulnerabilities and make it more difficult to mount attacks; deterrent measures that raise the cost on those who conduct malign influence operations; and resilience measures designed to inoculate societies and reduce the effectiveness of interference operations.

Defense

Effectively defending democracy requires defining democracy itself as a national security issue and putting its defense at the forefront of democratic governments’ national security agendas. Adopting whole-of-government approaches to this evolving threat and ensuring that governments are structured to both identify and respond to the full scope of foreign interference—eliminating the ability for issues to fall into bureaucratic seams—is a critical step. Robust defense will also require strengthened security for critical infrastructure, including electoral systems; strong anti-corruption and transparency measures; and the development of expertise and capacity to understand and track malign interference. Legal loopholes that authoritarians exploit need to be closed. The private sector also needs to play a central role in addressing the technological vulnerabilities that authoritarians exploit, and catching such vulnerabilities before they are exploited in the future. Furthermore, governments and the private sector need to increase cooperation to share information and defend against the threats of tomorrow.

Deterrence

Deterrence is also critical to countering foreign interference. Tactics like cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and economic influence tend be low cost and high reward compared to conventional measures. Democracies must raise the price of such operations by imposing costs on their perpetrators. That needs to start with clear deterrent messaging from senior leaders defining unacceptable conduct and delineating consequences for interference. These consequences could include economic, diplomatic, and reputational costs, though the most effective costs will be those tailored to specific adversaries’ weaknesses. Moreover, democracies should define their own asymmetric advantages and respond on those terms—not the terms set by authoritarians—and must ensure that responses are consistent with democratic values. Democracies must also stand together to share information about threats and coordinate responses, using mechanisms like that envisioned by the G7.

Adopting whole-of-government approaches to this evolving threat and ensuring that governments are structured to both identify and respond to the full scope of foreign interference—eliminating the ability for issues to fall into bureaucratic seams—is a critical step.

Resilience

Even with the best defenses and strong deterrence, authoritarian powers are unlikely to halt their assault on democracies. That’s why building resilience in democratic societies is critical to reducing the long-term effectiveness of these tactics. Transparency and exposure of interference operations imposes reputational costs on the adversary. Awareness of such operations reduces societies’ vulnerability to them and may help unite societies against external aggression. Media literacy education is another way to help inoculate against information operations, and strengthened civic education can remind citizens of what is at stake. Given that many interference efforts, particularly from Russia, aim to increase divisions in targeted societies, it is essential that any response not be partisan or used for partisan purposes. Finally, interference operations are most successful when they exploit existing vulnerabilities in democracies, and democratic societies must work to address these vulnerabilities and challenges in order to harden the target for authoritarian actors.

A Unified Effort

While authoritarian interference presents a range of challenges, democracies already have the tools necessary to mount effective responses—if they can muster the political will. Through a unified effort by governments, private sector actors, and civil society, democracies can ultimately strengthen themselves in the face of these threats.

Laura Rosenberger is director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy and a senior fellow at The German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF). Follow her on Twitter @rosenbergerlm.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Comments

MyBlog

August 14, 2025

itstitle

excerptsa